What Was Life Like for Australia's First Female Architect?

As a pioneering architect, engineer and urban planner, Florence Taylor built a foundation for female architects to come

Florence Mary Taylor (née Parsons), born in 1879, was a woman of many hats. She was the first qualified female architect in Australia, the first woman to train as an engineer in Australia and the first female to fly a glider in Australia. She was an editor and publisher, a businesswoman, feminist and well-known personality.

The odds were stacked against Taylor when she studied architecture in the early years of the 1900s. But Taylor’s defiant personality and visionary character saw her succeed in the face of these odds, building the foundation for female architects to come.

The odds were stacked against Taylor when she studied architecture in the early years of the 1900s. But Taylor’s defiant personality and visionary character saw her succeed in the face of these odds, building the foundation for female architects to come.

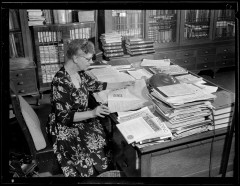

Image from The State Library of New South Wales. Florence Taylor, 1953.

In 1907 Taylor married artist, inventor, and craftworker George Taylor, who was equally passionate about architecture and town planning. Together they established the Building Publishing Co. Ltd, which produced trade journals such as Building, Construction and Australasian Engineer. These journals advocated for urban planning, better materials and construction methods, and promoted the best interests of engineers, architects and builders.

While Taylor said goodbye to being a practicing architect in 1907, her influence through the trade journals became her long-standing legacy. “We can’t overstate her significant contribution to architecture and the built environment through these publications,” says Binns.

The Taylors continued their publishing business throughout World War I, and after George died in 1928, Florence determinedly carried on through the Depression and World War II.

Taylor produced urban plans and travelled abroad to bring back progressive town planning ideas. She published these in her journals and the book Fifty Years of Town Planning With Florence M Taylor in 1958. As Hanna and Robert Freestone describe in Florence Taylor’s Hats (2008), many of these ideas eventually came to fruition in Sydney, including the harbour tunnel crossing, eastern suburbs distributor freeway, construction of ‘double-decker streets’, such as the Victoria Street overpass at Kings Cross, more apartment buildings, particularly in harbourside locations, and more flexible mixed-use zoning.

Find an architect near you on Houzz, browse images of their work and read past client reviews

In 1907 Taylor married artist, inventor, and craftworker George Taylor, who was equally passionate about architecture and town planning. Together they established the Building Publishing Co. Ltd, which produced trade journals such as Building, Construction and Australasian Engineer. These journals advocated for urban planning, better materials and construction methods, and promoted the best interests of engineers, architects and builders.

While Taylor said goodbye to being a practicing architect in 1907, her influence through the trade journals became her long-standing legacy. “We can’t overstate her significant contribution to architecture and the built environment through these publications,” says Binns.

The Taylors continued their publishing business throughout World War I, and after George died in 1928, Florence determinedly carried on through the Depression and World War II.

Taylor produced urban plans and travelled abroad to bring back progressive town planning ideas. She published these in her journals and the book Fifty Years of Town Planning With Florence M Taylor in 1958. As Hanna and Robert Freestone describe in Florence Taylor’s Hats (2008), many of these ideas eventually came to fruition in Sydney, including the harbour tunnel crossing, eastern suburbs distributor freeway, construction of ‘double-decker streets’, such as the Victoria Street overpass at Kings Cross, more apartment buildings, particularly in harbourside locations, and more flexible mixed-use zoning.

Find an architect near you on Houzz, browse images of their work and read past client reviews

Image from The State Library of New South Wales.

Taylor was a tall and striking woman who was also recognised for her decorative hats. She voiced strong and progressive opinions about the role of women in society, and believed women should contribute to public affairs.

Taylor was appointed OBE (Officer of the Order of the British Empire) in 1939 and CBE (Commander of the Order of the British Empire) in 1961, and was an honorary member of the Australian Institute of Builders and a fellow of the Royal Society of Arts, London. She retired in 1961 and died in 1969.

According to Hanna’s research, Taylor was one of only four qualified female architects in Australia between 1900 and 1919, along with Marion Mahony Griffin, Ruth Alsop and Beatrice Hutton. This number increased in coming generations, with 25 women qualifying as architects between 1920 and 1939, and 45 between 1940 and 1959.

While there has been improvement in the diversity of architecture, there is still a way to go. The American Institute of Architecture commissioned a study in 2016, Diversity in the Profession of Architecture. It found inequity between men and women as well as challenges to career advancement. The work-life balance impacted the representation of women, as did lower pay, lack of female role models, and leaving or returning to the industry due to maternity leave.

Taylor was a tall and striking woman who was also recognised for her decorative hats. She voiced strong and progressive opinions about the role of women in society, and believed women should contribute to public affairs.

Taylor was appointed OBE (Officer of the Order of the British Empire) in 1939 and CBE (Commander of the Order of the British Empire) in 1961, and was an honorary member of the Australian Institute of Builders and a fellow of the Royal Society of Arts, London. She retired in 1961 and died in 1969.

According to Hanna’s research, Taylor was one of only four qualified female architects in Australia between 1900 and 1919, along with Marion Mahony Griffin, Ruth Alsop and Beatrice Hutton. This number increased in coming generations, with 25 women qualifying as architects between 1920 and 1939, and 45 between 1940 and 1959.

While there has been improvement in the diversity of architecture, there is still a way to go. The American Institute of Architecture commissioned a study in 2016, Diversity in the Profession of Architecture. It found inequity between men and women as well as challenges to career advancement. The work-life balance impacted the representation of women, as did lower pay, lack of female role models, and leaving or returning to the industry due to maternity leave.

The Taylors had their office and residence in Loftus Chambers, adjacent to Circular Quay in Sydney. “There was a shift happening at the time as the area transitioned from a working harbour in the 1800s to a more commercial phase in the early 1900s,” says Binns.

The area is undergoing another significant transition today, and one that Taylor could have well been onboard with, given her town planning proposals for more harbourside residences and mixed-use zoning. Now known as Quay Quarter Sydney, the area is being transformed into a vibrant new precinct for living, dining, shopping and working.

The area is undergoing another significant transition today, and one that Taylor could have well been onboard with, given her town planning proposals for more harbourside residences and mixed-use zoning. Now known as Quay Quarter Sydney, the area is being transformed into a vibrant new precinct for living, dining, shopping and working.

A large number of people and practices are contributing to the development of Quay Quarter Sydney, which is centred around Young and Loftus streets.

It includes the revitalisation of two remaining old wool stores (Hinchcliff House and the Gallipoli Club), as well as a large-scale interpretation piece that commemorates and celebrates some of the key historical themes and personalities of the area. Binns conducted research about the history of the area and the personalities represented in this piece.

“Learning about Taylor was interesting from my point of view because it is usually men who are held up as the historical figures. It is important to bring diversity into the historical narratives with interesting female figures and indigenous people making contributions in the area,” says Binns.

It includes the revitalisation of two remaining old wool stores (Hinchcliff House and the Gallipoli Club), as well as a large-scale interpretation piece that commemorates and celebrates some of the key historical themes and personalities of the area. Binns conducted research about the history of the area and the personalities represented in this piece.

“Learning about Taylor was interesting from my point of view because it is usually men who are held up as the historical figures. It is important to bring diversity into the historical narratives with interesting female figures and indigenous people making contributions in the area,” says Binns.

Developers AMP Capital engaged new and emerging architecture practices, such as Silvester Fuller and Studio Bright, for buildings throughout Quay Quarter Lanes, as well as established firms such as ASPECT Studios and SJB. With women leading and in top management levels of these practices, Quay Quarter Sydney supports and promotes much-needed diversity.

The firm Silvester Fuller has designed 18 Loftus Street, which is one of a collection of three new apartment buildings in Quay Quarter Sydney.

“18 Loftus Street demonstrates the changes evident within the profession,” says Penny Fuller, founder and partner at Silvester Fuller. “Women were strongly represented among the project leadership team on both the client and consultant side, and our weekly Thursday meetings were often predominantly female. Now that the project is under construction, it is positive to see women are also strongly represented within the construction team too.”

Browse more beautifully designed living spaces

“18 Loftus Street demonstrates the changes evident within the profession,” says Penny Fuller, founder and partner at Silvester Fuller. “Women were strongly represented among the project leadership team on both the client and consultant side, and our weekly Thursday meetings were often predominantly female. Now that the project is under construction, it is positive to see women are also strongly represented within the construction team too.”

Browse more beautifully designed living spaces

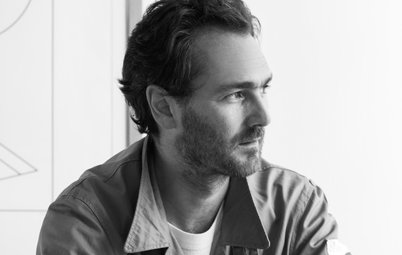

Penny Fuller of architecture firm Silvester Fuller.

Fuller says diversity has been valued in the design practices she has worked for throughout her career, and she and Jad Silvester have carried this experience into shaping the approach and studio culture at Silvester Fuller.

“In our practice we value diverse perspectives when we’re solving design challenges. This diversity extends across gender, age and cultural backgrounds,” says Fuller.

“It is a great time to be a woman in architecture as there is a ground swell of recognition currently occurring. However, my advice for anyone considering the profession – you need to love it. Architecture is a life that’s very demanding of your time, yet it can be highly rewarding if you are willing to put in the effort. As demonstrated by the Quay Quarter precinct, there are many opportunities within the construction industry for women across all aspects of projects.”

Fuller says diversity has been valued in the design practices she has worked for throughout her career, and she and Jad Silvester have carried this experience into shaping the approach and studio culture at Silvester Fuller.

“In our practice we value diverse perspectives when we’re solving design challenges. This diversity extends across gender, age and cultural backgrounds,” says Fuller.

“It is a great time to be a woman in architecture as there is a ground swell of recognition currently occurring. However, my advice for anyone considering the profession – you need to love it. Architecture is a life that’s very demanding of your time, yet it can be highly rewarding if you are willing to put in the effort. As demonstrated by the Quay Quarter precinct, there are many opportunities within the construction industry for women across all aspects of projects.”

Studio Bright, established by Melissa Bright, designed the residential building 8 Loftus Street, inspired by the rich detailing of great Art Deco buildings.

Melissa Bright of architecture firm Studio Bright.

“The conversation about capability is fixated on the wrong elements – it’s about hiring talent. I would like to be considered an architect who is very good at what she does, and I happen to be a woman,” says Bright.

“It is important to nurture, employ and mentor women because biases continue to exist. Female architects are strong, independent thinkers. They are determined to get to where they are meant to be, and the industry is much better for it.”

Your turn

What positive and progressive experiences have you had working with women in architecture and design? To help mark International Women’s Day, tell us in the Comments below, like this story, save the images, and join the conversation.

More

Have you met this dynamic duo taking the residential building, design and architecture industry by storm? Find out more in Candid Company: The Empowering Women Behind BuildHer Collective

“The conversation about capability is fixated on the wrong elements – it’s about hiring talent. I would like to be considered an architect who is very good at what she does, and I happen to be a woman,” says Bright.

“It is important to nurture, employ and mentor women because biases continue to exist. Female architects are strong, independent thinkers. They are determined to get to where they are meant to be, and the industry is much better for it.”

Your turn

What positive and progressive experiences have you had working with women in architecture and design? To help mark International Women’s Day, tell us in the Comments below, like this story, save the images, and join the conversation.

More

Have you met this dynamic duo taking the residential building, design and architecture industry by storm? Find out more in Candid Company: The Empowering Women Behind BuildHer Collective

Taylor was born in 1879 in England. Her family migrated to Sydney in 1884 and her father found work as a draftsman-clerk with Parramatta Council. Taylor’s father encouraged her to “do something constructive in life,” she recalled. “One day you might be a draughtsman like I am, or even an architect,” he had said to her. Following the deaths of her father and mother in the late 1890s, Taylor took inspiration from her father and found work to support herself and her two younger sisters. She became a draftsman-clerk in the Parramatta architectural practice of Francis Ernest Stowe, an acquaintance of her father.

In 1899, Taylor enrolled in architecture night classes at Sydney Technical College (STC), and received training under the architect Edmund Skelton Garton. She completed her training in 1904, becoming the first woman in Australia to be a qualified architect. For women to study, let alone complete their studies, was a rarity in the first decades of the 20th century. In her PhD dissertation Absence and Presence, A Historiography of Women Architects in NSW 1900-1960, architectural historian Bronwyn Hanna found that only 65 women were recorded in the exam register at STC between 1918 and 1954 (averaging just 3.2 percent of students). Of these, only 13 of them reached final year status.

Taylor began working for architect John Burcham Clamp in 1906, reportedly becoming the chief draftsperson. In 1907, she applied to become the first female member of the New South Wales Institute of Architects but faced considerable resistance from the all-male membership who did not want to admit a woman. In 1920 Taylor was eventually invited to join the Institute of Architects. She joined as an associate member and was admitted as a full member – and the first female member – in 1923.

“Taylor wasn’t practising as an architect at this time and therefore didn’t really have need for the credibility that membership gave. Rather she pursued this to lay the groundwork for other women coming up in the ranks,” says Fiona Binns, associate director and heritage consultant at Urbis in Sydney.

Male opposition was a common refrain around the world for women entering architecture, which was then perceived as a male domain, like most professions. Louise Blanchard Bethune was the first woman to be voted in as a member of the American Institute of Architects in 1888, and Ethel Mary Charles was the first female architect to be admitted to the Royal Institute of British Architects in 1898. Both also encountered resistance and prejudice in the industry.

“There was prejudice that women couldn’t handle the tricks of the trade; that women shouldn’t be on building sites; that they couldn’t manage construction projects or negotiate price,” says Binns. “There was also pay disparity, of course, and architecture offices often didn’t have facilities for women so they had to leave the building to go to the bathroom or wash their hands.”

Despite the challenges, Taylor built a thriving practice in just a few short years. Between 1900 and 1907 Taylor designed up to 100 houses. She worked with Clamp on the basement of the Farmers Department store in Pitt Street, and provided a perspective drawing for the winning competition entry for the Commercial Traveller’s Building in Sydney (which was demolished to make way for the MLC Centre in the 1970s).